Passion of Christ

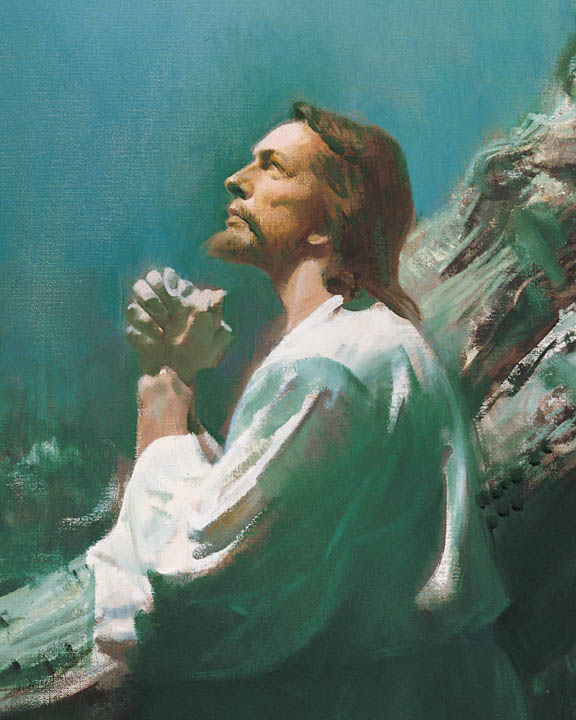

The Book of Mormon also backs up this belief in Mosiah 3:7, so members of the Church of Jesus Christ believe it was there in the Garden that He underwent his greatest suffering for men, taking upon himself, as he did, their sins on condition of repentance (D&C 18:10–15). This difference, alone, might not mean much because no one's salvation depends on which place and what time he suffered the most, and Latter-day Saints and non–Latter-day Saints alike appreciate Christ's suffering.

However, there arises from this difference on Christ's Passion some things that are perhaps more significant. One is the use of the cross as a religious symbol, which arose as a result of the association of Christ with it. Latter-day Saints interpret non–Latter-day Saints as trying to sensitize themselves to Christ's exquisite suffering by displaying the cross ever before them. However, many Latter-day Saints are already extremely sensitized—some might say, hyper-sensitized. Members of the Church of Jesus Christ view displaying the cross as similar to having a much loved family member shot or knifed and then having to see a gun or knife—or their loved one being shot or knifed—always before their view. The cross was the murder weapon which killed someone they love with all their hearts. Latter-day Saints flinch from seeing it. It sears their sensitive feelings about his suffering. They feel grief when they are reminded of his torture and death. Latter-day Saints much prefer to think of Christ's overcoming death than of his suffering death. They like to think of his triumph, not his suffering and seeming defeat. Likewise, while Latter-day Saints may have paintings of Mary, the apostles, etc. on the walls of their meetinghouses, temples, and homes, they do not display icons of them anywhere because they focus on Christ alone as Redeemer and Advocate. Christ is central to all aspects of Latter-day Saint worship: prayer in His name, baptism in His name, and praise to His name.

Gordon B. Hinckley, a past president of the Church of Jesus Christ, related the following experience and his testimony:

- Following a complete renovation of one of our temples, nearly a quarter of a million people saw its beautiful interior. Among these was a Protestant minister who said:

- “I’ve been all through this building, this temple which carries on its face the name of Jesus Christ, but nowhere have I seen any representation of the cross, the symbol of Christianity. I have noted your buildings elsewhere and likewise find an absence of the cross. Why is this when you say you believe in Jesus Christ?”

- I responded: “I do not wish to give offense to any of my Christian brethren who use the cross on the steeples of their cathedrals and at the altars of their chapels, who wear it on their vestments, and imprint it on their books and other literature. But for us, the cross is the symbol of the dying Christ, while our message is a declaration of the living Christ.”

- He then asked, “If you do not use the cross, what is the symbol of your religion?”

- I replied that the lives of our people must become the only meaningful expression of our faith and, in fact, therefore, the symbol of our worship.

- I hope he did not feel that I was smug or self-righteous in my response. He was correct in his observation that we do not use the cross, except as our military chaplains use it on their uniforms for identification. Our position at first glance may seem a contradiction of our profession that Jesus Christ is a key figure of our faith. The official name of the church is The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. We worship him as Lord and Savior. The Bible is our scripture. We believe that the prophets of the Old Testament who foretold the coming of the Messiah spoke under divine inspiration. We glory in the accounts of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, setting forth the events of the birth, ministry, death, and resurrection of the Son of God, the Only Begotten of the Father in the flesh. Like Paul of old, we are “not ashamed of the gospel of [Jesus] Christ: for it is the power of God unto salvation” (Rom. 1:16). And like Peter, we affirm that Jesus Christ is the only name “given among men, whereby we must be saved” (see Acts 4:12).

- The Book of Mormon testifies of him who was born in Bethlehem of Judea and who died on the Hill of Calvary. To a world wavering in its faith, it is another and powerful witness of the divinity of the Lord. Its very preface, written by a prophet who walked the Americas a millennium and a half ago, categorically states that it was written “to the convincing of the Jew and Gentile that JESUS is the CHRIST, the ETERNAL GOD, manifesting himself unto all nations.”

- And in the Doctrine and Covenants, He has declared himself in these certain words: “I am Alpha and Omega, Christ the Lord: yea, even I am he, the beginning and the end, the Redeemer of the world” (D&C 19:1).

- In view of such testimony, well might many ask, as my minister friend asked, if you profess a belief in Jesus Christ, why do you not use the symbol of his death, the cross of Calvary?

- To which I must first reply, that no member of this Church must ever forget the terrible price paid by our Redeemer who gave his life that all men might live—the agony of Gethsemane, the bitter mockery of his trial, the vicious crown of thorns tearing at his flesh, the blood cry of the mob before Pilate, the lonely burden of his heavy walk along the way to Calvary, the terrifying pain as great nails pierced his hands and feet, the fevered torture of his body as he hung that tragic day, the Son of God crying out, “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34).

- This was the cross on which he hung and died on Golgotha’s lonely summit. We cannot forget that. We must never forget it, for here our Savior, our Redeemer, the Son of God, gave himself as a vicarious sacrifice for each of us. . . .

- On Calvary he was the dying Jesus. From the tomb he emerged the living Christ. The cross had been the bitter fruit of Judas’ betrayal, the summary of Peter’s denial. The empty tomb now became the testimony of His divinity, the assurance of eternal life, the answer to Job’s unanswered question: “If a man die, shall he live again?” (Job 14:14).

- Having died, he might have been forgotten, or, at best, remembered as one of many great teachers whose lives are epitomized in a few lines in the books of history. Now, having been resurrected, he became the Master of Life. . . .