Clay County

Clay County Missouri is a significant location in the early years of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. From approximately June 1834 until 1836, the Missouri Saints escaped the persecution they had endured in Jackson County by settling in Clay County. The citizens of Liberty, the seat of Clay County, charitably offered shelter, work, and provisions. But the established citizens of the county also reminded the Saints that they were permitted to stay only until they could return to Jackson County. Through the efforts of Alexander Doniphan, Ray County, Missouri, was divided into two new counties named Caldwell and Daviess. The Saints were permitted to establish a community in Far West, Caldwell County, approximately 60 miles north of Clay County.

- The Lord commanded Joseph Smith to gather a group of men to march from Kirtland to Missouri to help the Saints who had been driven from their lands in Jackson County. When Zion's Camp reached eastern Clay County, Missouri, in late June 1834, a mob of over 300 Missourians came out to meet them—intent on their destruction. Under the direction of the Prophet Joseph, the brethren set up camp at the junction of the Little and Big Fishing Rivers.[1]

- The mob began to attack with cannon fire, but the Lord was fighting the battle of the Saints. Clouds quickly began to form overhead. The Prophet described the circumstances: “It began to rain and hail. … The storm was tremendous; wind and rain, hail and thunder met them in great wrath, and soon softened their direful courage and frustrated all their designs to ‘kill Joe Smith and his army.’ … They crawled under wagons, into hollow trees, filled one old shanty, etc., till the storm was over, when their ammunition was soaked.” After experiencing the pelting of the storm all night, “this ‘forlorn hope’ took the ‘back track’ for Independence, to join the main body of the mob, fully satisfied … that when Jehovah fights they would rather be absent. … It seemed as if the mandate of vengeance had gone forth from the God of battles, to protect His servants from the destruction of their enemies.”[2]

Perhaps most significant is the experiences of Joseph Smith and others during the winter of 1838–1839 when they were incarcerated in Liberty Jail, which was located in Clay County. In a worldwide Church Educational System fireside, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland summarized the events leading up to Joseph’s arrest.

- Time does not permit a detailed discussion of the experiences that led up to this moment in Church history, but suffice it to say that problems of various kinds had been building ever since the Prophet Joseph had received a revelation in July of 1831 designating Missouri as the place “consecrated for the gathering of the saints” and the building up of “the city of Zion” (D&C 57:1, 2). By October of 1838, all-out war seemed inevitable between Mormon and non-Mormon forces confronting each other over these issues. After being driven from several of the counties in the western part of that state and under the presumption they had been invited to discuss ways of defusing the volatile situation that had developed, five leaders of the Church, including the Prophet Joseph, marching under a flag of truce, approached the camp of the Missouri militia near the small settlement of Far West, located in Caldwell County.[3]

- As it turned out, the flag of truce was meaningless, and the Church leaders were immediately put in chains and placed under heavy guard. The morning after this arrest, two more Latter-day Saint leaders, including the Prophet’s brother Hyrum, were taken prisoner, making a total of seven in captivity.[4]

- Injustice swiftly moved forward toward potential tragedy when a military “court” convened by officers of that militia ordered that Joseph Smith and the six other prisoners all be taken to the public square at Far West and summarily shot. To his eternal credit, Brigadier General Alexander Doniphan, an officer in the Missouri forces, boldly and courageously refused to carry out the inhumane, unjustifiable order. In a daring stand that could have brought him his own court-martial, he cried out against the commanding officer:

- It is cold-blooded murder. I will not obey your order. . . . And if you execute these men, I will hold you responsible before an earthly tribunal, so help me God.

- In showing such courage and integrity, Doniphan not only saved the lives of these seven men but endeared himself forever to Latter-day Saints in every generation.[5]

- Their execution averted, these seven Church leaders were marched on foot from Far West to Independence, then from Independence to Richmond. Parley P. Pratt was remanded to nearby Daviess County for trial there, and the other six prisoners, including Joseph and Hyrum, were sent to Liberty, the county seat of neighboring Clay County, to await trial there the next spring. They arrived in Liberty on December 1, 1838, just as winter was coming on.[6]

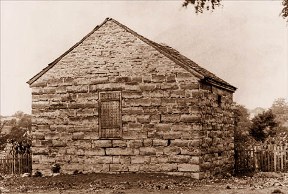

As the men awaited trial, they suffered severe privation. “Confined to the lower level or dungeon portion of the building, they slept on the straw-strewn stone floor with little light and scant protection from the Missouri winter. Alexander McRae described the food they were served as ‘very coarse, and so filthy that we could not eat it until we were driven to it by hunger’ (CHC 1:521).”[7] Scholar and professor Alexander Baugh suggests that the men were allowed upstairs during the day where there was a stove to provide some heat, but there was little outside light and the space was confined.

- Conditions in the jail were miserable. Joseph Smith wrote, “We are kept under a strong guard, night and day, … our food is scant, uniform, and coarse; we have not the privilege of cooking for ourselves, we have been compelled to sleep on the floor with straw, and not blankets sufficient to keep us warm; and when we have a fire, we are obliged to have almost a constant smoke.”[8]

- Relief came from visits of friends and family. Hyrum Smith remembered, “Many of our brethren and sisters call to see us and to administer to our necessities.” According to Alexander McRae, visitors “brought us refreshments many times” with some bringing “cakes, pies, etc., and handed them in at the windows.” The visitors who brought the greatest joy to the prisoners were members of their immediate families. Emma Smith visited the jail three times, once bringing Joseph and Emma’s son Joseph III. Hyrum’s wife Mary Fielding Smith visited her husband with their infant son, Joseph F. Smith. This was the first time Hyrum had met his son.[9]

- As their time in the jail lengthened and the majority of Saints fled the state, the number of visitors declined. Receiving letters became one of the few things that lifted the prisoners’ spirits. But letters also brought heartbreak as the prisoners learned of the conditions many Saints were in as they left Missouri for Illinois during the harsh winter months.[10]

“Notwithstanding these trying physical conditions, Joseph Smith's greater suffering seemed to come from his anguish for the thousands of Latter-day Saints, including his own family, who were being driven from the state under the executive order of Governor Lilburn W. Boggs calling for the extermination of the Mormons.”[11]

Joseph wrote a very long, two-part letter to the Church in March 1839 and petitioned God for divine intervention. Doctrine and Covenants section 121 is the answer to his prayer. Excerpts from his letter make up sections 121, 122, and 123 of the Doctrine and Covenants.

In February, Sidney Rigdon was set free because of severe illness. In April, the others were taken to Daviess County, then while being moved to another venue, they were encouraged by their guards to escape. They joined the Saints who were gathering in Illinois.

‘’’See also’’’ Liberty Jail, Extermination Order