Great Salt Lake

The Great Salt Lake is the largest lake west of the Mississippi River and the largest salt water lake in the Western Hemisphere. It is one of the saltiest bodies of water in the world because, in part, it does not have an outlet.

At its average level at 4,200 feet above sea level, it is 75 miles long and 35 miles wide at its widest point. At its greatest depth, it is approximately 34 feet deep. The average depth is only 14 feet. During its recorded low in 1963, some of the lake's 10 major islands became peninsulas. In 1983, when the lake reached its historic high, it flooded houses, farmland, and the nearby freeway. Huge pumps were constructed to deposit excess water into Utah's west desert. The pumps were shut down in 1989.[1]

The Bear River, the Jordan River, the Ogden River, and the Weber River feed the Great Salt Lake, as do numerous streams. (The Jordan River is the only outlet of Utah Lake.) The surface area of the Great Salt Lake changes due to snow run off, rain, and evaporation. The salt flats that surround the lake are often flooded by the fluctuating lake level.

The lake, although as much as 27 percent salinity (saltier than the ocean’s 3 percent), forms a complex ecosystem. “The ever-fluctuating Great Salt Lake has frustrated attempts to develop its shoreline. As a result much of the lake is ringed by extensive wetlands making Great Salt Lake one of the most important resources for migrating and nesting birds.”[2] A few of the most common are barn owl, American avocet, bald eagle, snowy plover, golden eagle, and pelicans.

Contents

The Great Salt Lake and the Mormon Pioneers

The valley of the Great Salt Lake was an anticipated haven for the beleaguered members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The imposing Rocky Mountain Range created a barrier between the Saints and their persecutors. But the land was arid, and one of the advance party described it as “a broad and barren plain hemmed in by mountains ... the paradise of the lizard, the cricket and the rattlesnake”[3] Brigham Young and other Church leaders had heard reports of the valley that Kit Carson and John C. Fremont had explored in 1843 and 1845.[4] And so the pioneers streamed into the valley, first arriving in July 1847.

The pioneers immediately began turning the desert into productive land by creating irrigation from the creeks, streams, and rivers flowing from the nearby Wasatch Mountains.

- In July 1847, four days after the Latter-day Saints reached what they called the Great Salt Lake Valley, President Young and pioneers were floating in the briny lake, reported historian John L. Clark.

- “We took our dinner at the freshwater pool and then rode six miles to a large rock on the shore of the Salt Lake which we named Blackrock, where we all halted and bathed in the salt water,” future church president Wilford Woodruff wrote. “No person could sink in it but would roll and float on the surface like a dry log. We concluded that the Salt Lake was one of the wonders of the world.”[5]

Their new city was called Great Salt Lake City until they dropped “Great.” Utah Territory and parts of neighboring states, in time, became the refuge that the Saints were looking for.

Ancient History

Some 10,000 to 30,000 years ago, prehistoric freshwater Lake Bonneville once covered 20,000 square miles of much of the western portion of Utah, reaching into Nevada and Idaho. Its shorelines included many islands and peninsulas. Shorelines of Lake Bonneville can be seen as shelves or benches above Salt Lake City. The Stansbury, Bonneville, and Provo shorelines are also seen in satellite images.

After the overflowing phase about 15,000 years ago, Lake Bonneville went through a regressive phase, and a warmer and drier climate caused the lake to diminish to roughly 2/3 of the maximum depth.

Utah Lake and Sevier Lake are also remnants of Lake Bonneville.

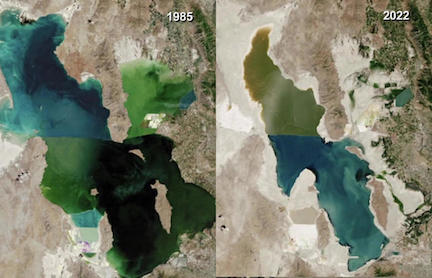

Drought

The topic of the 2023 Stegner Symposium was the future of the Great Salt Lake, which the United States Geological Survey says is at a historic low elevation. A severe drought has gripped much of the western United States for many years. Researchers at Brigham Young University (BYU) say that without a dramatic increase in water, the lake could be gone in as little as five years. And that disappearance could cause significant damage to Utah’s public health, environment, and economy.

Speaking at the 28th annual Wallace Stegner Center Symposium at the University of Utah on Friday, March 17, 2023, Bishop W. Christopher Waddell of the Presiding Bishopric of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints outlined this history and the Church’s current and future water conservation efforts. He described the “continual and ongoing Churchwide effort to improve our care of natural resources, including the implementation of best practices and available technology to improve our water efficiency.”

“We are committed to be a part of the solution to help the Great Salt Lake and have made some initial efforts to contribute,” Bishop Waddell said.

Those efforts include the donation announced on March 15, 2023, of the Church’s water shares in the North Point Consolidated Irrigation Company — possibly the largest permanent donation of water to benefit the Great Salt Lake that Utah has ever received. The 20,000 acre-feet donated are equivalent to a water supply for 20,000 single-family homes.

He also mentioned research by BYU faculty that helps Church leaders and others know how to best save the Great Salt Lake.

“We are indebted to the subject matter experts who study the conditions of the Great Salt Lake and the impacts and future risks of its declining water levels,” Bishop Waddell said. “We encourage engagement and responsiveness to legislative changes and other recommendations from subject matter experts recognizing the need to act with urgency and unity towards the future we hope for — one with a healthy Great Salt Lake.”

He also detailed the Church’s other water conservation plans.

In addition to all the Church has done and is doing to conserve water, Bishop Waddell said prayer is critical and has proven providential.

In June 2022, the Church invited Latter-day Saints to “join with friends of other faiths in prayer to our Heavenly Father for rain and respite from the devastating drought.” The invitation emphasized that “we all play a part in preserving the critical resources needed to sustain life — especially water — and we invite others to join us in reducing water use wherever possible.”

The Utah Department of Natural Resources reported that as of March 16, 2023, water content in the snowpack across Utah is at an all-time high for the date.[6]

The snowpack is much needed and appreciated because, at the record low set in November 2022, the Great Salt Lake was 4,188.2 feet above sea level, down from the historic high of 4,211.6 feet set in 1986.

Islands in the Great Salt Lake

The Great Salt Lake has 17 officially named islands, but due to the changing elevation of the lake, there are usually less. These include, Badger, Strongs Knob, Cub (Greater Cub and Lesser Cub), Egg, Carrington, Hat, Dolphin, and Gunnison. Often left out of the count are Black Rock, White Rock, Browns, Rock, and two Goose Islands. The three main islands are Antelope Island, Fremont Island, and Stansbury Island. The major islands and some of the minor ones are actually mountain ranges that poke up above the lake.

There is an artificial island known as Goose Egg, which was formed from the May 1983 Rudd Canyon debris flow, which was hauled and piled up in Farmington Bay. Mud Island in Ogden Bay was designated on maps for about 100 years. Two other islands, Newfoundland and Little Mountain, were islands for a time.

Antelope Island, named by John C. Fremont, is the largest island in the lake where Heber P. Kimball, Lot Smith, and Fielding Garr brought cattle belonging to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Mormon pioneer Garr built a ranch house, and the Fielding Garr Ranch is still open to tourists. Antelope Island State Park offers hiking, camping, and sailing. The island is also home to bison, antelope, deer, bobcats, coyotes, elk, and waterfowl.

Stansbury Island is named for Howard Stansbury, who surveyed the area in 1850. The island has a 9-mile mountain biking trail. It has wildlife, including deer, lizards, wild turkeys, jackrabbits, and hawks. There are private property sections of the island, but enough public land for parking, hiking, biking, rockhounding, and camping. It also hosts pink water near its shoreline due to the brine shrimp in the lake.

Fremont Island has been privately owned by different groups or individuals. In 2020, the land was donated by a private donor to the State of Utah, Division of Forestry, Fire & State Lands. Although the island is managed as public, the Nature Conservancy holds a conservation easement designed to protect the land from development or damage. Public access is allowed, although there are warnings and rules for visitors.[7] Walking and biking are allowed.

Unique Features at the Great Salt Lake

- Spiral Jetty, an earthen sculpture by Robert Smithson built in 1970, is visible when the Great Salt Lake level is below 4,195 feet elevation.

- Bonneville Salt Flats stretch over 30,000 acres west of the lake. The arid plain where the Black Pearl is beached in Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest was filmed here. The Bonneville Speedway is located in the western portion, where numerous land speed records have been set.

- The railway causeway that divides the Great Salt Lake creates blue water on the side where salt water mixes with fresh and pink on the saltier side that hosts salt-loving organisms.

- Saltair Pavilion was a resort completed in 1893 and owned jointly by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Salt Lake and Los Angeles Railway. It was built in the early 20th century Moorish Revival architectural style. Constructed on 2,000 posts and pilings, it was intended to mirror the East Coast’s Coney Island. It was a popular family destination for a time. The Church sold the resort in 1906. It burned in 1925, was rebuilt, but burned again in 1931. It closed during World War II and was destroyed by arson in 1970. The third Saltair was built in 1981 and serves as a music venue.[8]

External Sources

- Utah State Parks, “Great Salt Lake”

- Wikipedia, “Lake Bonneville”

- Utah Geological Survey, “How Many Islands Are in Great Salt Lake?” by Jim Davis

- Church Newsroom, “Bishop Waddell Talks Water Conservation in the Church of Jesus Christ”

- Deseret News, “What early church leaders said about the Great Salt Lake,” by Tad Walch

- Utah History Encyclopedia, “Irrigation in Utah,” by Craig Fuller