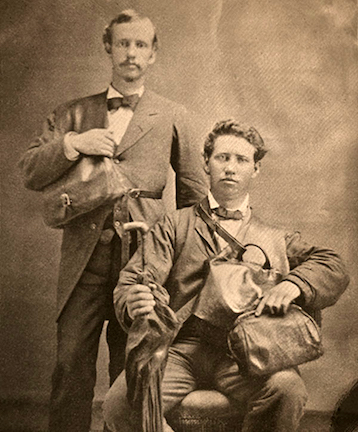

Joseph Standing

Joseph Standing was serving as a missionary in the Southern States Mission when he was killed by a mob near Varnell’s Station, Whitfield County, Georgia.

Standing was born on October 5, 1854, in Salt Lake City, Utah Territory. He lived in Box Elder County, Utah, and worked as a fireman with the Wasatch Engine Company. He served a mission to the Eastern States in 1875.

He had served a mission to the Southern States Mission from October 1875 to September 1876. He was serving a second time, beginning in March 1878. Standing, along with fellow missionary Matthias F. Cowley, were sustained as the 'traveling Elders' of the Southern States Mission.

By April 1879, Standing was the presiding Elder of the Georgia Conference, responsible for overseeing all church affairs in the state. That same month, at a general conference of the church in Salt Lake City, 22-year-old Rudger Clawson was called with seven other men to serve in the Southern States Mission. Clawson was assigned by mission president John Hamilton Morgan to be Standing's companion.

By at least 1876, Standing's letters were periodically published in the Deseret Evening News. One published on April 30, 1878, provides insight into his experiences in the post-Reconstruction South.

- A person traveling among the Southern people realizes that though they have been whipped by the North, yet there is a feeling of enmity existing in their bosoms, which only needs a little breeze to inflame their passions to deeds of carnage and strife.[1]

Local opposition to the Church of Jesus Christ increased as Standing and other elders increasingly gained converts in rural areas in North Georgia.

As the threat of violence toward Latter-day Saints increased, Standing sent a letter to Georgia Governor Alfred H. Colquitt on June 12, 1879, briefly outlining the activities of armed mobs in Whitfield County and requesting assistance.

- I am fully aware dear Sir, that the popular prejudice is very much against the Mormons, and that there are minor officers who have apparently winked at the condition of affairs above referred to. But I also am aware that the laws of Georgia are strictly opposed to all lawlessness and extend to her citizens the right of Worshipping God according the dictates of conscience. . . A word or line from the Governor would undoubtedly have the desired effect. Ministers of the Gospel could then travel without fear of being stoned or shot and the houses of the Saints would not be entered into in defiance of all good law and order.

Although the Governor responded with the commitment to “instruct the State Prosecuting Attorney for the District to inquire into the matter,” Standing and Clawson met with an angry mob on their way to a meeting in Rome, Georgia.

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland recalled in General Conference the moment of Elder Standing’s death.

- At that time in America’s history, well over one hundred years ago, malicious mobs were still in existence, outlaws who threatened the safety of members of the Church and others. Elder Clawson and his missionary companion, Elder Joseph Standing, were traveling on foot to a missionary conference when, nearing their destination, they were suddenly confronted by twelve armed and angry men on horseback.

- With cocked rifles and revolvers shoved in their faces, the two elders were repeatedly struck, and occasionally knocked to the ground as they were led away from their prescribed path and forced to walk deep into the nearby woods. Elder Joseph Standing, knowing what might lie in store for them, made a bold move and seized a pistol within his reach. Instantly one of the assailants turned his gun on young Standing and fired. Another mobber, pointing to Elder Clawson, said, “Shoot that man.” In response every weapon in the circle was turned on him.

- It seemed to this young elder that his fate was to be the same as that of his fallen brother. He said: “I … at once realized there was no avenue of escape. My time had come. … My turn to follow Joseph Standing was at hand.” He folded his arms, looked his assailants in the face, and said, “Shoot.”

- Whether stunned by this young elder’s courage or now fearfully aware of what they had already done to his companion, we cannot know, but someone in that fateful moment shouted, “Don’t shoot,” and one by one the guns were lowered. Terribly shaken but driven by loyalty to his missionary companion, Elder Clawson continued to defy the mob. Never certain that he might not yet be shot, young Rudger, often working and walking with his back to the mob, was able to carry the body of his slain companion to a safe haven where he performed the last act of kindness for his fallen friend. There he gently washed the bloody stains from the missionary’s body and prepared it for the long train ride home (in David S. Hoopes and Roy Hoopes, The Making of a Mormon Apostle: The Story of Rudger Clawson, New York: Madison Books, 1990, pp. 23–31).[2]

“Clawson contacted Henry Holston, two miles away, and Holston agreed to go to the site of the incident and look after Standing's body while Clawson rode a horse to Catoosa Springs to contact the coroner (approximately 8 miles from Holston's home). Before returning with the coroner, Clawson sent the following telegram to Governor Colquitt in Atlanta; ‘Joseph Standing was shot and killed to-day, near Varnell's, by a mob of ten or twelve men.’ He sent the same message to John Hamilton Morgan in Salt Lake City with the additional line; ‘Will leave for home with the body at once, Notify his family.’”[3]

“When they reached the spring, the mob had dispersed and a crowd of spectators were gathered around Standing's body. The body now had more than 20 bullet wounds in the face and neck. It is believed this was done by the mob to protect the original shooter from conviction by having each man participate in the crime.”[4]

Standing ’s funeral was held in the 12,00-seat Salt Lake Tabernacle on August 3, 1879. One report said the number attending was 5,000, another said 10,000. Transcripts of the talks by John Taylor and George Q. Cannon were published in the Deseret News and later the Journal of Discourses.

Governor Colquitt offered a $500 reward for the capture of the “murders of the Mormon elder,” thirteen warrants for arrest were issued by the local sheriff, and three men were indicted by a grand jury for first degree murder and riot. The accused, however, were acquitted of murder and riot.

In 1880, a monument was placed over Standing’s grave in Salt Lake City. A replica of the original marker, including an iron fence around the base, replaced the broken marker in 2001. The monument bears this inscription:

- MARTYRED For the testimony of Jesus, while with Elder Rudger Clawson, through whose heroism the body was afterwards rescued, July 21st, 1879, Varnell Station Whitfield Co. Ga. by a armed mob of twelve men named David D. Nation, Jasper N. Nation, A.S. Smith, Daniel Smith, Bedj. Clark, W.M. Nation, Andrew Bradley, Jon Forssett, Hugh Blair, Jos Nations, Jefferson Hunter, Mark McClure

- HIS MURDERERS were indicted and two of them tried, the first upon a charge of murder and the other for riot. Through bigotry and prejudice, both were acquitted. Evidence of guilt was not lacking, but the assassins boasted, "There is no law in Georgia for the Mormons."

On May 3, 1952 church president David O. McKay dedicated a monument at the site of Standing's murder in Whitfield County, Georgia. The 0.68-acre lot was donated to the church by W. C. Puryear and the road leading to the monument was named Standing Road. The property is maintained by the church and open to the public.[5]

- This Memorial Park and monument honor the memory of Elder Joseph Standing of Salt Lake City, Utah, a missionary of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, (Mormon) who was killed here by a mob July 21, 1879. His companion, Elder Rudger Clawson who later became president of the Council of the Twelve Apostles of the Church was unharmed. The cooperation of W. C. Puryear and family who donated the land and were most helpful in other ways, made this memorial possible.